Women Who Changed History for the Good of Humankind

On August 8, 2024 by msdarcyonlineThere were countless women who broke the mold of the prescribed role of women in the early, high, and later Middle Ages. The resourceful women of the Viking Age, the women visionaries of Medieval Europe, as for example Hildegard of Bingen, and Margery Kempe, as well as the heroic Joan of Arc. These women were unusual for the time they lived in, and they were important to their societies and how they served them.

In the history of Scandinavia, the period that experienced the most radical change was the Viking Age (AD 750-1100). Women played a large part in the voyages of raiding, expansion, trading and settlement. This provided women with new opportunities and gave them authority in the most important matters of daily life. Norse women had an unusual degree of freedom for women of their day and age. They could own property, request a divorce and reclaim their dowries if their marriages ended. If the man of the household was absent or deceased, the wife had complete authority to run the farm and trading business.

There is evidence that Viking women played an active role in Viking colonization and traveled with the men on Viking boats sailing to Europe and arriving in England in the 860s and 870s; as well as to Russian and North America; and, in the late 9th century, the first settlers were Norwegian Vikings.

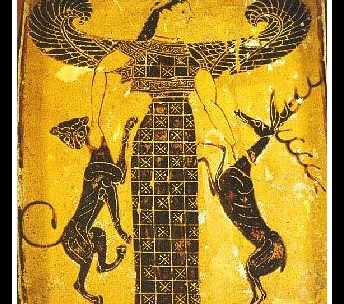

Valkyries, or shieldmaidens, are an important part of old Norse literature. Some women in Viking society fought in battle. Lagertha, the shieldmaiden, fought alongside King Ragnar Lothbrok in a battle against the Swedes. Ragnar later married Lagertha because he was so impressed by her courage. There are historical records of women fighting with Swedish Varangian Vikings in a battle against the Bulgarians in AD 471, or in the battle of Bravellin in the mid 8th century. In Norse mythology, the Valkyries decided the fate of men; who would be killed in battle, and who would survive. In some cases, they might even determine the outcome of the battle. They took their chosen half of men from battle to the afterlife hall of the slain, Valhalla. The goddess Freyja would take the other half of the slain to the ‘Field of the Warriors.’ Freyja was the mythological role model for the Valkyrie, and a war goddess.

In Old Norse poems, the Valkyries were equated to Ravens and understood the speech of birds, so they were considered to be wise. This was like Odin’s Huginn and Munnin, the two ravens who flew around the world and collected information for Odin, they represented thought and memory, and Odin had given them the capability to speak.

Some writings suggest that because the Viking mind was a product of a militarized culture, they imagined women warriors, which can be seen in their art and mythology. Medieval history was written by men, for men; therefore, very few historical records mention the role of women in Viking warfare, but there is historical proof that Viking women were ready to fight to protect their land and homes when necessary.

The Volva, or the Norse witch, were predominantly women, and might be the equivalent of a shaman. Volvas belonged to the highest level of society and were cultivated and protected throughout history by German tribes. They served Freyja, also known as the mythological Goddess of Love in Asgard, and Odin, the God of Wisdom, Poetry and War. Volva was the Goddess of Love in Midgard, or on earth, but she was not harmless and used a wand as a weapon.

In the poem “The Prophecy of the Volva,” a volva foresees and visualizes the entire history of the universe from beginning to end. As the poem is spoken by the witch, this means that the entire poem is an example of a séance, or a connection to the Gods through ritual and the art of psychic prophecy. The Volva would perform High Seat Ceremonies, during which the community would assemble and debate important matters. The idea was that information is transformation, so the ceremonies were intended to send the Volva to a specific place where answers to their questions could be found. It was very valuable for their people and communities to be able to obtain information from the Gods was extremely prized. Both Freyja and the ancient volva, created the familial path of the witch and her magical arts.

In the course of Christianization in the 10th century, the Goths were the first Germanic tribe to convert to Christianity and pursue and oppress their witches. The Christian Church enacted laws against them, and they were killed. However, in Norway, conversion to Christianization was slow, and in Bergen there is evidence that as late as the 13th century, Norse mythology was still followed and practiced. In Iceland, the literary works “Edda,” which contained material from the Viking age and Norse mythology, begins with “The Prophecy of the Volva,” and was first written in the 13th century.

In 1066, at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, the last Viking incursion ended. King Haraldr of Norway was killed and his troops driven back when he attempted to reclaim a portion of England. The Viking age ended as the raids ended; they were no longer lucrative and not in agreement with the fundamentals of the Christian Church. Times changed, but the Vikings had not been conquered, and they became Swedes, Danes, Norwegians and Icelanders.

Throughout history, prophecy was one area in which women were seen as superior to men. From the classical period, the Greeks called women who were prophets, ‘The Sibyls.’ In the book “Aeneid,” Aeneas consults the Greek Sibyl, who predicts the Trojan War, so Aeneas asks to see his father. The Sibyl directs him into the underworld where he sees his father, and looks into the future. Then there was also Cassandra, who predicted the destruction of Troy, and was given her power to reveal the future by Apollo.

Women prophets were revered and honored in Celtic, Germanic and Scandinavian legend. Wise women, priestesses, and witches were able to travel alone and live without fear. The Volva-Norse Witches were well-versed in magic and possessed great powers. They were in demand as shamans, healers, prophets and wise women. They were wives of God and lived outside and above the normal hierarchy of society. In the Middle Ages, prophets and visionaries were considered to be divinely inspired teachers and consulted as spiritual guides.

In the Scriptures, there are several prophetesses who were inspired by God: Mary, sister of Moses; Deborah, the only woman judge of Israel; Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist; Hannah and Anna.

In late Medieval Europe, where most women were not allowed to speak in public or write unless they were from noble families, prophets were able to play a direct role in politics. An Apocalyptic Visionary, or divinely inspired prophetic observer, revealed the mysteries and fate of human life. They were writers who revealed existential truths. Whereas prophets just spoke the word of God and did not write.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), an apocalyptic visionary who was called the ‘German Sibyl,’ was also a talented poet and music composer. She claimed to have secret knowledge about the cosmos, the history of the world and the coming of the Antichrist. She was certain she could decipher the mysteries of the Scriptures, and said she heard a voice that told her to “tell these marvels and write them.”

St Bridget of Sweden (1303-1373), whose revelations and predictions were extremely precise, and St Catherine of Siena (1347-1380), a mystic and spiritual writer, whose daring ideas were extremely persuasive in politics and world history, both conveyed their visions to scribes, although St Catherine eventually learned how to write.

Margery Kempe was a Medieval prophet (1373-1438), who gave the world the first autobiography in English. Kempe accurately predicted future events and had epiphanies about the fate of the dead. She claimed she had visitations and conversations with Jesus Christ and God, and possessed the ability to see the secrets of people and their true moral character. Her supernatural abilities to experience God through bodily and ghostly visions, gained her many followers. Her book includes her experiences during pilgrimages to the Holy land, Italy and Spain, and describes her spiritual crusade. Although she was perceived to be by many as a delirious woman, her book shows us otherwise; it is a complex and thorough description of the life of a middle class laywoman from the Middle Ages. Her intellectual enlightenment gave her a true understanding of her own spirituality. Her book is a historical document and gives her a place in Christian history.

Joan of Arc saved France and became a legend, heroine, martyr and saint. As the patron saint of France, Joan is a permanent symbol of French nationalism and unity. Joan of Arc (1412-1431) was the daughter of a farmer and village official who had a minor role collecting taxes. They lived in the eastern part of France in an isolated area. Joan did not know how to read or write, but she had been instilled with a deep love for the Catholic Church and its teachings. When Joan was thirteen, she started to hear voices and see visions of saints, which she resolved were voices from God giving her a very important mission: to save France and expel its English enemies and bring back Prince Charles’ legitimacy and make him king. Part of her divine mission included taking a vow of chastity. When she was 16, her father tried to choose a husband for her, but she convinced the court that she should not be forced to accept the partner.

According to popular prophecy, the virgin was to save France. Joan claimed to be the virgin and attracted followers. She tried to get an audience with Prince Charles, but that was too complicated, so she cut her hair and dressed like a man and made her way to the Prince’s court.

When Joan was finally received by Charles in his court, he asked for concrete proof that she could fulfill the prophecy. Joan spoke of Charles’ intimate prayer, and she was able to convince him. A few days earlier, Charles had begged God to give him a sign of legitimacy. He had received the sign he had been looking for from Joan, as only a messenger of God could know the information Joan had given him.

Charles put together an army. Joan’s presence revolutionized the soldiers: she boosted their morale with her confidence and determination. Dressed in white armor and riding a white horse, Joan and the army set off to defeat the English. Despite having been wounded by an arrow in her neck, Joan ended a year-long blockade in the town of Orleans in just four days. After what appeared to be a miraculous victory, Joan’s reputation spread among French forces. Several short, rapid victories followed for Joan and the French forces. She then opened the way to Reims, along with her followers, through enemy territory to Reims where Charles was crowned king.

Joan had a deep, emotional effect on the forces. She advised the commanders, who believed her advice was divinely inspired. Their decisions were based on her advice and proved to be very successful. Joan wanted to take back Paris, but Charles was against it. Joan had become very powerful, but enemy forces had strengthened their positions in Paris, and Joan had to turn back. In Joan’s final battle at Compiegne, she was defeated by the English and delivered to their hands. Sent to trial, the judge tried to discredit Joan in the eyes of her compatriots. To the English, the abilities of this uneducated peasant girl were proof she was possessed by the devil. The idea that God might be on the side of the French was unacceptable to the English. The judge wanted to provide the English with a forced and fake confession that Joan’s voices and the angel that had guided her to her victories, was not God’s archangel Michael, but the fallen angel Lucifer. She was charged with heresy, witchcraft and dressing like a man. The French king Charles never made any attempt for her release and betrayed her.

Joan’s resistance was totally heroic and she challenged her judges, she never gave up her fighting spirit. They were unable to force a confession from her for one year, until finally under threat of death, she relented and signed a confession that she had never received divine guidance. Days later, she defied her captors and dressed in men’s clothes again. The authorities condemned her to death and at the age of 19, she was burned at the stake.

Joan’s death inspired courage in French forces and her victory in Orleans had paved the way for the final victory of the French. King Charles successfully returned to the battlefield capturing major cities that were under English rule. Twenty years later, Charles convened an investigation to scrutinize Joan’s trial. Her unjust judgment was declared null and baseless, and she was declared innocent in 1456.

These women were extraordinary for the time they lived in and they were important and made a difference with their contributions to their societies and how they represented them. Viking women had a lot of personal freedoms and rights compared to other women in Europe in the Middle Ages. Women visionaries in countries, such as France, Germany, Sweden, and England accurately predicted future events, and they were intellectually and spiritually enlightened. They all learned how to write, contrary to most women of their time so that they all earned their place in history because of their personal writings, and not male scribe interpretations. And, Joan of Arc saved France from English conquest. All of these women mentioned made history and contributed to making their societies more open-minded and reasonable, and at the same opened doors for women in their own place and time.

References:

Acker, Paul, Larrington Carolyne, “The Poetic Edda: Essays on Old Norse Mythology.” Series: Routledge Medieval Casebooks, Routledge. 2015. eBook. Database eBook Collection EBSCOhost.

Brown, Callum G., “Nordic Religions of the Viking Age.” Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Jan. 2002, Vol. 53, Issue 1, p137. EBSCOhost.

Flanagan, Sabina, “Hildegard of Bingen.” Rutledge, 2nd edition, 1998. ebook //doi.org/10.4324/9780203007297.

Newman, Barbara, “Sibyl of the Rhine.” Hildegard’s Life and Times, Teoksessa Newman (ed.)[1998]1998: 1-29.

Guerard, Albert, J., Michelet, Jules, “Joan of Arc.” The University of Michigan Press, 1967.

Watt, Diane, “Secretaries of God: Women Prophets in Late Medieval and Early Modern England, D.S. Brewer, 1997.

Young, Serinity, “Women Who Fly: Goddesses, Witches, Mystics and Other Airborne Females, Oxford University Press, 2018.

Related

Written by msdarcyonline

Recent Posts

- Animal Welfare and Animal Rights May 10, 2025

- The End of an Epoch January 5, 2025

- Women Who Changed History for the Good of Humankind August 8, 2024

- Paul Cezanne : Father of Modern Art June 16, 2024

- Humans’ Unjust Dominance Over Animals. February 20, 2024

Archives

- May 2025

- January 2025

- August 2024

- June 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- June 2023

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- February 2022

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- September 2020

- August 2020

- June 2020

- March 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- August 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017